This article opens by tracing the evolution of the art market in India, reviewing the literature on how the factors defining it changed from aesthetic to commercial, and on the role of the government in promoting art. Taking the city of Delhi as a case, the growth of the art market is mapped through the spread of galleries across different sites. We then look at the evolution of four private galleries from being just exhibition spaces to art consultants/advisors/art evaluators/art research and documentation centres.

Evolution of the art market in India

In the 1990s, together with changes happening in every field in post-liberalization India, the character of the art world shifted from aesthetic to commercial. Laura Chaudhary-Haberl, an old collector, describes the art scene in the post-independence period in Bombay (Haberl 2002:50–51). She reminisces that in ‘those days’ art was not seen as an investment. Art was bought for art’s sake, and never in the belief that the painting would be worth much more in value in future. In fact, she points out that no one ever thought that paintings would ever be worth anything. Visitors to their house always wondered if anybody would actually be willing to spend money on modern Indian art. Jehangir Art Gallery was practically the only venue for exhibitions in those times. The Artists’ Aid Centre was small and commercial galleries hardly existed, except for the Taj Art Gallery and then Gallery Chemould (from the mid-‘60s). Art lovers also regularly visited the artists’ studios. There were just a handful of art galleries till the 1980s.

In the past two decades, the art market in India has changed completely. The growth of galleries in the 1990s and especially in 2000s is an evidence of the evolution of the market. Geeta Kapur (2000) linked the growth to the economic liberalization policies, and to the ‘enormous, two-hundred-million strong middle class’:

As part of its self-legitimizing process, as part of its multinational corporate identity, and, finally, as a result of its investment interests, there is now a fairly flourishing art market in India. … This is the upwardly mobile middle class that is, for the first time, testing its identity vis-à-vis the world. In addition to the middle class, the globalizing Indian bourgeoisie and the NRIs (non-resident Indians) have come into the picture and now constitute the largest section (ninety per cent) of the international buyers. All these categories of buyers need the national/ Indian slogan to shore up their self image, their consumer status and cultural confidence.’ (Kapur 2000:87)

Kapur also comments on the impact of international auction houses like Christie’s and Sotheby’s, which held their first auctions of contemporary Indian art in 1987 and 1989, and were decisive in raising the market value of Indian art works and the rise of ‘a new breed of galleries and collectors’. From around ten private and commercial galleries in 1990, India had around 200 by 2000; in the same decade, prices of a considerable range of artists went up ten to twenty times (Kapur 2000).

The success of the art market can be gauged by the people involved in the sector. As Poulsen (2010) observes, the people involved in the present art scenario often have not spent their lives in India. The market has grown to the extent that now it interests foreigners and the NRIs, as is evident with the presence of Peter Nagy (Nature Morte), Bharti Kher and others in the Indian art sector.

Poulsen criticizes the limited number of museums in India as compared to Europe, and also the lack of transparency and public information on numbers and specifics. She points out that most frequently circulated guesstimates of the size of the Indian art market claim a growth from US$2 million in 2001 to US $400 million before the recession in 2008. Sotheby’s December 2000 auction, which sold 193 lots of Indian art, is regarded as a landmark event marking a sudden increase in the international interest in Indian art (Chong and Robertson 2008, cited in Poulson 2010). The two Indian auction houses Saffronart and Osian’s were established that same year (Poulson 2010:188). These numbers alone confirm the expansion of the Indian art market, which is also evident in the number of major shows on contemporary Indian art by prestigious art institutions all over the world.

Kapil Chopra (2010:100) notes that as the prices soared 500% in 2003, so did the number of galleries go up manifold as well. He takes Bodhi Gallery as a leading example of the art market’s rise and fall.

Between 2004 to 2010, one of the most prominent poster boy galleries of the Indian contemporary art space came and then shut shop but left a big mark on the scene. Bodhi Art Gallery came in with a flourish in 2004 and changed the rules of the game, the artists were flown business class to art openings, the galleries looked good and the staff even better, the catalogues were of a quality that I do not even see till now. Due to all these ancillary costs prices went through the roof and artists on Bodhi roster went up 500% in months. It fuelled a boom and speculation in the contemporary art space which was never seen before. After four years of a heady rise, the recession hit and in a speculative market where positions had to be unwound, Bodhi finally shut shop. (Chopra 2010:100)

The period of recession after the spectacular growth of the art market resulted in the closing down of Osian as well. Several people saw it as inevitable given the sudden rise of the market, and some even called it better for sustainability. As Anders Patterson (2010:55) comments, Indian art has been virtually absent from the auction market since September 2008; where it accounted for 51% of the overall value of Modern and Contemporary Art, it only accounts for 9%. It actually demonstrates that the market has moved to the primary market.

Recent trends

Raqs Media Collective founded in 1992 and Khoj in 1997 by Pooja Sood are examples of alternative spaces for today’s artists which promote experimentation with new media. Kakar (2010) observes that Indian artists of the 1990s introduced new material and media into their art practice, thereby altering both the prevailing viewership and the conventions of display.

In the present age of digitization, online sites are becoming as significant and popular as gallery spaces. Gallerists are spending on websites as it connects them to a wider audience not just in India but around the world as well.

Lately, to attract more crowds, art galleries have been organizing their space around building cafes, book shops, and art shops within their premises, Religare art, Vadehra Art Gallery being examples. Also, in the 2000s many corporate houses joined the art bandwagon as well, like Bajaj (Art Positive), Jindal (Steel) and Religare.

Art patronage by the state

In an article of 1960 (cited in Kakar 2010), Ram Kumar discussed the various forms of state patronage for artists: the setting up of public galleries to promote visual arts, e.g., the Lalit Kala Akademi in Delhi (August 1954) and the National Gallery of Modern Art (which opened in Delhi in 1954, while branches at were set up in Mumbai and Bangalore in 1996 and 2009). Kumar refers also to the government promoting art by purchasing works by contemporary artists for Indian embassies and by commissioning decorative work on government buildings or government-sponsored exhibitions (Kakar 2010).

Lalit Kala Akademi

Lalit Kala Academi was composed of a General Council which included art practitioners, theorists and appointed representatives of the government. The bursaries and scholarships by cultural wings of various governments had expanded the opportunities for artists to travel and exhibit immediately after independence. The Akademi channelled its resources into providing a community space for artists to create, exhibit and meet.

Since its inception the Akademi held annual national exhibitions. In the late 1960s, it expanded its role by initiating the first Indian triennale (1968), an international exposition of art which brought the works of artists of over 40 countries to India on a regular basis. While none passed without an artists’ protest against organizational deficiencies, jury selections and approbation through monetary awards, these triennales gave artists in India the opportunity to view a diverse range of works, and also to develop a robust public sphere where artists collectivized and rallied against institutions, exhibitions and manifestos.

Regional aspirations meant that the Akademi had to initiate the Kala Mela, a festive, tented exhibition space to house the works of artists across the country who sought visibility during the triennale. In New Delhi, the Garhi Artists’ Village Complex built in 1976, for example, provided an ideal ‘retreat’ from the chaos of the city, where a community print-making studio, a casting foundry, and a ceramic workshop were set up to cater to the needs of working artists’ (Karode and Sawant 2009:194).

Sinha (2003:127) talks about the history and the relationship of artists with the triennale. The first was preceded by a protest meeting at the Delhi Silpi Chakra where Tyeb Mehta, J. Swaminathan and Krishen Khanna openly criticized the event (all three were to receive awards for painting at the Triennale). Criticisms of the process of selection snowballed in the second triennale into active protests and an artists’ boycott. Swaminathan, Geeta Kapur and Vivan Sundaram questioned the cult of internationalism fostered by such events (quoted in The Times of India, Delhi, 31 January, 1971). In Baroda, Gulam Sheikh and Bhupen Khakhar’s magazine initiative Vrishchik became the nodal point for institutional criticism and sought to represent an alternative credo. The protest of the artists who organized themselves into the Council of Indian Artists (CIA) nearly led to the cancellation of the third triennale in 1975, by which time artists had broadly concurred on setting up alternate fora for participation, even as they devised alternate strategies for art practice.

In 1977, Geeta Kapur curated the exhibition Pictorial Space for the Lalit Kala Akademi. Sinha (2003) says this was the first of the curatorial initiatives by an individual within the official framework which led to the Festival of India exhibitions in London, Paris and Washington DC in the 1980s. Pictorial Space was followed in 1982 by Contemporary Indian Art, an exhibition for the Festival of India exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, curated by Akbar Padamsee, Richard Bartholomew and Geeta Kapur. According to Dalmia (2002), a new internationalism emerged with the Festivals of India, which fostered greater awareness and opportunities for Indian artists to interact with other countries. Sponsored by a special commission headed by Pupul Jayakar, the Festivals served to place Indian contemporary art among other forms on a wider platform.

Moving to the present, government policy on art needs to be revisited. ‘Gallery’ is not even defined legally. The absence of laws has sometimes benefited the cause of art (e.g., has helped in the mushrooming of galleries) and often harmed it, e.g., buyers of art get no tax concessions. Bringing in art from abroad attracts a 52% tax. This often leads to bizarre situations where artists returning from shows abroad have to pay to bring back their own art works, as Bhupen Khakhar once did. However, a gallery association has been formed to act as a pressure group for authorities to formulate a policy to boost art (Dutta 2000:66).

Overall, the field of art, even though it is in a state of flux, is in a better situation today than it was a couple of decades back. There is now an institutionalization of art activity and the art sector is more organized.

Problems

There are still some areas that need serious consideration. For example, as Johny ML (2010) notes, the same artists get awards simultaneously or in successive years. Most times, it is the same panel that selects the awardees. There is a huge gap between the artists who have made it big (the minority) and those who are still struggling to make it.

Auctions by the international auction houses led to an insane rise in prices of artworks. Mary Ann Dasgupta, an old collector from Kolkata says she stopped buying art in the early 1980s when the price boom began, because she simply could not afford it (Sarkar 2001). There is no basis for fixing the prices; according to Kapil Chopra (2010:100), ‘paintings are priced on the basis of how many ladies are painted in the painting, 1 lady for 3 lacs and 2 for 5 lacs!’ Many galleries in present times, like Delhi Art Gallery and Saffron art auction house have started providing art valuation services to promote a proper pricing model.

Galleries in Delhi

Galleries are mushrooming in the capital, hoping to cash in on the art market boom. ‘Affordable art' has become the keyword to expand the base of the art-buying public. In a bid to sell art at affordable rates, many big and small galleries have opened shop with emerging and established artists slowly becoming part of them.

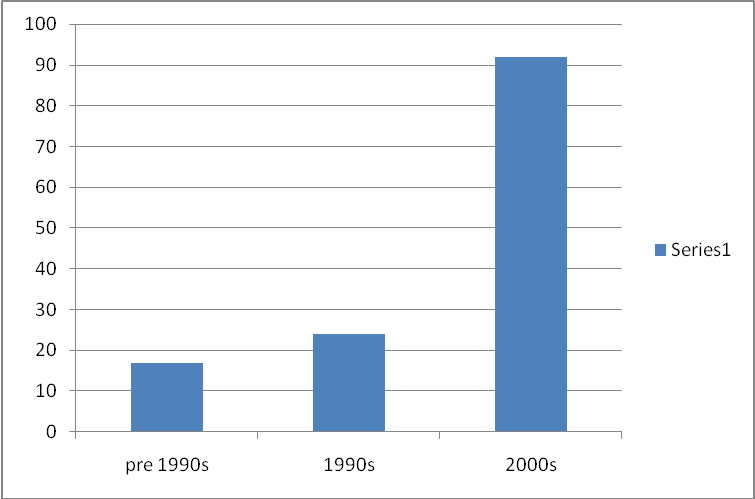

Fig. 1: The rise in the number of art galleries over the years

The above diagram shows the phenomenal rise in the number of galleries in the decade 2000–2010. There were just a handful of galleries before the 1990s. The trend changed in the 1990s, a lot of galleries came up (some also closed down in recession of 1997-98) but the true growth can be seen in the new century. In 2001, Archies Cards also opened its own gallery, Epiques in Okhla Industrial Area. In 2011, an advertising agency launched a gallery (which sells artwork of its artist employees) in South Extension and promised ‘affordable art’ starting from prices as low as Rs. 5,000. The boom in the art market is especially visible in areas like Lado Sarai, Hauz Khas Village, Shahpur Jat (now referred to as ‘art districts’), apart from the main commercial areas like Connaught Place, Greater Kailash I and II and Khan Market.

Menezes (2008) thinks the Commonwealth Games were responsible for this. She says in the run up to the Commonwealth Games (2010), there was a major drive to shut down commercial establishments located in residential/institutional areas. Faced with the risk of closure, galleries were forced to move out from the city’s centre to its periphery. Consequently, they have shifted to industrial areas, to pockets of ‘lal dora’ land (the revenue term for abadi areas or rural settlements as listed in 1908, many of which have been absorbed by the city and are termed ‘urban villages’) and even to the NCR region to the satellite towns of Gurgaon and Noida. Galleries have more space at their disposal now that they have shifted from cramped residential quarters to factory-like spaces.

The search for space has also prompted some galleries like Gallery Nvya to go truly commercial and move into Delhi’s mushrooming malls. Some might argue that it is good for galleries to have a presence at more public venues so that they can reach out to a wider audience. Chawla Art gallery has its branches in a mall and in a hotel in Saket.

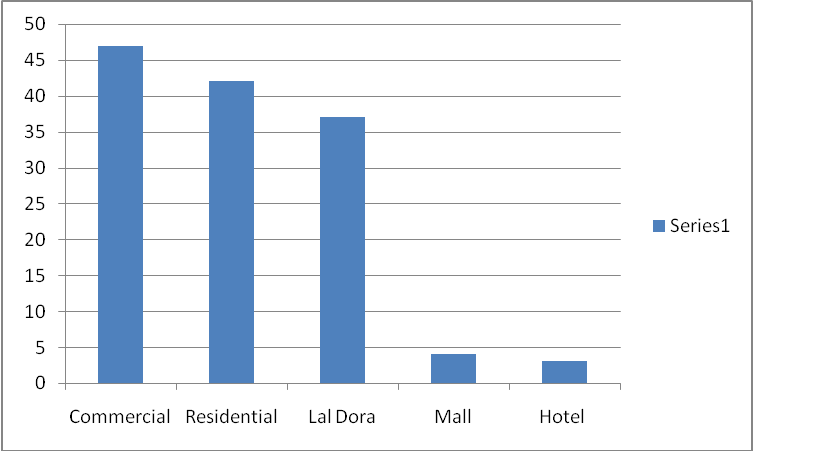

Figure 2: Division of galleries across different locations in Delhi

The above diagram shows the galleries spread across the city in different locations. Most of the small galleries that came up in the 2000s have mostly been in lal dora areas, a new category that is unique to the city of Delhi. Similarly, malls are new options to open galleries in. Hotels are also going with the trend and providing space to showcase art.

Galleries in lal dora areas

Menon (2008) explains the uses of ‘lal dora’ land, a term first used in 1908 for that part of the land where villagers used to maintain support systems like livestock, and which was demarcated from agricultural land by the revenue department by tying a red thread (‘lal dora’ in Hindi). The area is under the direct control of the Gram Sabha/ Panchayat, and cannot be acquired by anyone, not even the government. Municipal laws are not applicable here. Permitted uses of lal dora land include building a house, without any requirement to apply for sanctions for building plans, which is why it is a popular investment proposition. What is not allowed is commercial activity. Lal dora land costs less, there is no limit to the number of plots one can own, and it is not required to pay property tax (originally there were no maps of individual plots, nor written records of ownership; it was the villagers who knew which part was owned and occupied by whom).

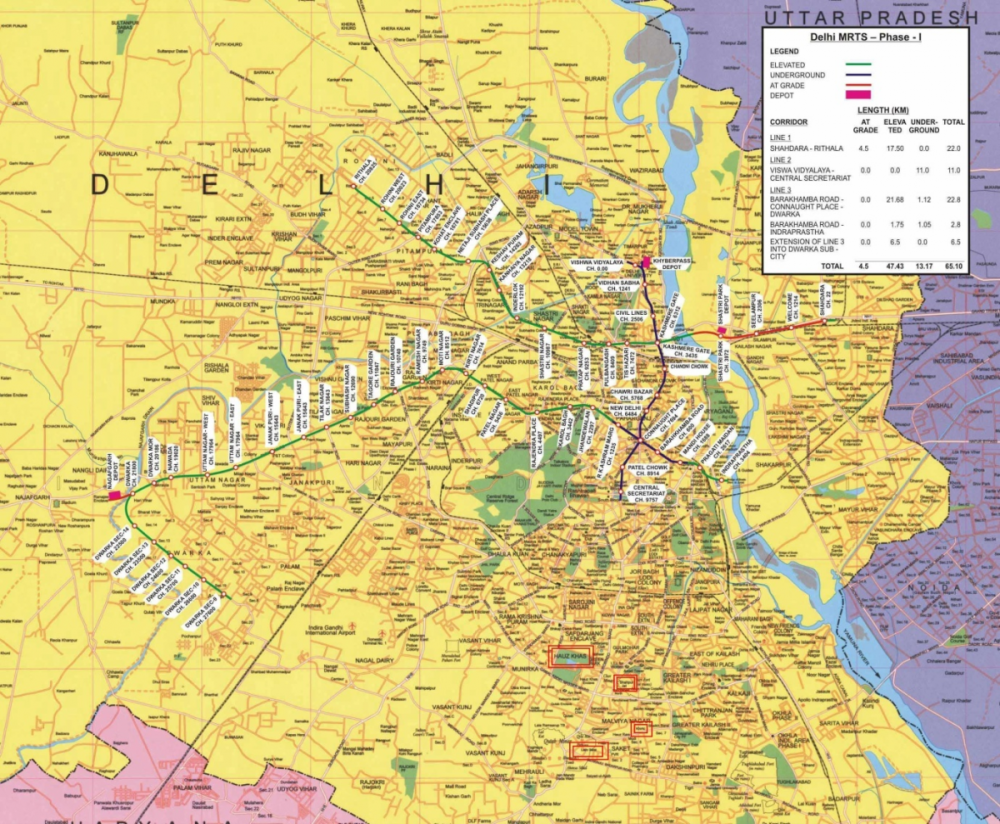

Today, many areas of Delhi that are still classified as lal dora include high end commercial and residential areas. Many are extremely well connected, with facilities provided by the government, like secure electricity connections, water from the Delhi Jal board, sewerage, etc. Hauz Khas Village, Khirkee Extension, Shahpur Jat and Lado Sarai are lal dora areas where many small galleries are located. A number of galleries now in close proximity to each other in Lado Sarai, like Gallery Threshold, Gallery Art Motif, Artpilgrim Art Gallery and Anant Art Gallery, Latitude 28 are working together to promote the area as an art hub. The emergence of these clusters of galleries relates to the fact that these areas fall in south Delhi, arguably the most affluent and posh part of the city, and the flexibility in the rules governing the use of lal dora land.

Sketches of four galleries in Delhi

Vadehra

From its inception in 1987, Vadehra Art Gallery (VAG) has been come one of the most important galleries in India, and since 2006, it has been especially active. It was the first to go into art publishing in 1996, and has published monographs on artists, books on art making, picture books and a comprehensive art directory. Vadehra has participated in art fairs in Spain, Dubai, New York, Hong Kong, Shanghai, and, in addition to exhibiting in foreign shores, has worked with NGMA and Lalit Kala Akademi. Shows increased from 2006, when Vadehra collaborated with the Grosvenor Gallery to form Grosvenor Vadehra in London. Grosvenor Vadehra had three inaugural exhibitions of Indian art: ‘The Moderns Revisited’, ‘Inverting/Inventing Traditions’ and ‘Here and Now: Young Voices from India’, and also convened the first Pablo Picasso exhibition held in a private gallery in India. The same year saw the launch of the Foundation for Indian Contemporary Art (FICA) to support artists and educational activities in the visual arts. August 2008 saw the opening of the Vadehra Art Gallery Book Store, which combines a reading room/library space by FICA and a bookstore.

In an interview, Arun Vadehra reminisces that ‘…the first show was, appreciated but not a single frame sold. There was no market for art in those days! Eventually we decided to keep one work each of the artists’ and from there began our gallery’s private collections...’ (Vadehra 2010).

In another interview, Sunil Gupta, curator with Vadehra, talked about the second gallery that opened in 2005 in Okhla to exhibit new works by upcoming artists while the Defence Colony branch still showed ‘mainstream commercial art’. In July 2009, VAG opened its fifth space at DLF Emporio Mall in Delhi. This space functions both as a contemporary art gallery as well as an exclusive store selling art books, products and accessories.

Espace

Gallery Espace was established in New Delhi in 1989 by Renu Modi with an exhibition of autobiographical works of M.F. Husain. It showcased other artists of the 1980s as well: J. Swaminathan, Manjit Bawa, Krishen Khanna, Bhupen Khakhar and Vishwanadhan. Under Renu Modi, Espace can be credited with organizing curated exhibitions, probably some of the first in the Indian art scene.

Espace’s history shows a preference for solo shows as compared to group shows (20-30) and very few curated shows. Espace’s busiest year was 2007 when it had 26 exhibitions, with 18 solos and eight group shows curated by Gayatri Sinha and Roobina Karode among others.

Anant

It has been a very busy gallery since its inception in 2008 in a lal dora area, Lado Sarai. In the first year itself they had eight exhibitions. 2009 was the busiest year which saw 19 exhibitions, nine solo shows and the remaining group shows.

Delhi Art Gallery (DAG)

The Delhi Art Gallery was started by Rama Anand in 1993. Ashish Anand, director, DAG, took over the gallery from his mother in 1996. Its collections range from the early moderns to the moderns, including all the masters and senior artists to more recent contemporary art. Delhi Art Gallery owns its entire, comprehensive collection. From 1999 to 2010 it has hosted 25 exhibitions. Apart from the display of art works, DAG also provides art valuation, consultation, art preservation services.

Conclusion

The rise in the number of exhibitions shows how active the art scene has been since 2005. Galleries are now participating in art fairs around the world, which has exposed them to international trends. In keeping with the times, gallery owners are also more willing to showcase video and performance art. They are now working with public institutions for major exhibitions. Examples include the Raghu Rai Retrospective, which Bodhi Art sponsored at the NGMA in 2008, and Anupam Sud’s show sponsored by Palette Art Gallery at the Lalit Kala Akademi in 2007. Gallery owners in Delhi have started to network with galleries in other cities to organize travelling exhibitions of contemporary Indian Art. Vadehra Bookstore and reading room (FICA in Defence Colony) shows how galleries are also investing in documenting art and academics. New art schools are coming up all over India. An interesting feature is the presence of women in the field of arts, as artists, gallery owners and curators. But it remains a field restricted to that stratum of society which does not have to worry about its livelihood.

Fig. 3: Galleries in lal dora areas (which emerged mainly in 2000s)

References and Further Reading

Bucher, Victor. 1989. 'Art and Cultural Sponsorship "Austrian-style", International Journal of Museum Management and Curatorship:77–82.

Chopra, Kapil. 2010. 'Basement Galleries and Beyond' in Take 2:100–01.

Dalmia, Yashodhara. 2002. 'Introduction' in Contemporary Indian Art and Other Realities, ed. Yashodhara Dalmia. Delhi: Marg.

Dutta, Rita. 2000. 'Pushing back the Frontiers' (on Rakhi Sarkar), in The Art News Magazine of India 5.2:66–68.

Haberl, Laura Chaudhary. 2002. 'A Progressive Patron', in The News Art Magazine of India 7.3:50–53.

Kakar, Bhavna. 2010. 'Editorial', in Take 2:8–10.

Kapur, Geeta, 2000. 'What’s New in Indian Art: Canons, Commodification , Artists on the Edge' in Reflections on the Arts in India, ed. Pratapaditya Pal. Mumbai: Marg Publications.

Karode, Roobina, and Shukla Sawant. 2009. 'City Lights, City Limits: Multiple Metaphors in Everyday Urbanism', in Art and Visual Culture In India 1857–2007, ed. Gayatri Sinha. Mumbai: Marg Publications.

M.L., Johny. 2010. 'Art, Ideology and Galleries', in Take 2:39–41.

Menezes, Meera. 2008. 'Capital Spaces' in The News Art Magazine of India 13.2:26–31.

Menon, Rakesh. 2008. ‘What is Lal Dora: Delhi Master Plan’. Online at http://www.articlesbase.com/real-estate-articles/what-is-lal-dora-land-delhi-master-plan-513135.html (viewed on November 7, 2016).

Moore, James. 2004. 'The Art of Philanthropy: The Formation and Development of the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool', in Museum and Society 2.2:68–83.

Patterson, Anders. 2010. Untitled in Take 2:55–56.

Poulsen, Nina, 2010. 'Creative Tensions: Contemporary Fine Art in the "New" India' in A New India? Critical Reflections in the Long Twentieth Century, ed. Anthony P. D’Costa. Delhi: Anthem Press.

Sarkar, Shiladitya. 2001. 'Beauty with Dignity' (on Mary Ann Dasgupta), in The Art News Magazine of India 6.1:62–65.

Seth, Swapan. 2010. 'On-the-go + On-the-Way+ Out-of-the-way in Take 2:98.

Sinha, Gayatri, 2003. 'The 1970s: Simultaneous Streams' in Indian Art: An Overview, ed. Gayatri Sinha. Delhi: Rupa Publishers.

Vadehra, Arun. 2010. Take 2.

Websites

Gallery Espace. http://www.galleryespace.com

Vadehra Art Gallery. http://www.vadehraart.com

External Links: Galleries Lists

Anand Foundation

http://www.anandfoundation.com

DAG Modern

http://www.delhiartgallery.com

This article was written as a part of research on the IFA-CCMG-Jamia Millia Islamia project on Exhibition and Curatorship Policy Research and Advocacy (2011). I would like to thank IFA-CCMG team for their helpful insights and suggestions.